Discussion:

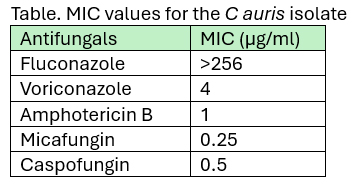

Correct answer: 2. Based on the provided antifungal susceptibilities, it is reasonable to continue intravenous micafungin at this time as long as the candidemia is not persistent and we have good source control.

Answer 1 is not correct. Liposomal amphotericin B can be considered as a treatment option if the echinocandin MIC is elevated1 and if the patient has persistent candidemia for more than 5 days. While there are currently no established susceptibility breakpoints for C auris, breakpoints have been proposed based on those established for closely related Candida species and expert opinion. Therefore, breakpoints should be considered as a general guide. The current Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) interpretation of antifungal MICs for C auris addresses rezafungin, with a breakpoint of ≤0.5 µg/ml (M27M44S) for susceptible isolates.4 CDC lists tentative breakpoints for amphotericin B (≥2 µg/mL) and other echinocandins, with tentative breakpoints for micafungin and caspofungin of 4 and 2 µg/mL, respectively.5 Therefore, based on the current knowledge of C auris antifungals MICs and breakpoints, and the antifungals MICs provided above, stopping micafungin and changing to liposomal amphotericin B is not warranted.

Answer 3 is not correct. This answer explores the idea of synergistic activity of combining antifungals against C auris. Also, having an oral antifungal (in this case, voriconazole) as an option may facilitate the patient’s care up to hospital discharge. However, the case presents a fluconazole-resistant isolate, and there is limited clinical knowledge about breakpoints for other triazoles in the case of C auris, as well as the clinical efficacy of voriconazole in such cases. CDC guidelines do not list a breakpoint for voriconazole; therefore, this option is not favorable.5

Answer 4 is not correct. Based on the provided MICs, there is no indication to add liposomal amphotericin B. However, in cases of persistent candidemia for several days (≥5 days) or an echinocandin-resistant isolate, switching to liposomal amphotericin B or attempting a combination of different antifungals may be considered. However, very limited clinical data are available to support such a clinical decision.1,2 Another option to explore, especially if the C auris isolate is pan-drug resistant, is to consider an investigational agent through expanded access programs for fosmanogepix or ibrexafungerp.1,6