A 17-year-old Male Patient with AML Presenting With a Suspected Fungal Infection in the ICU

Presented by Dr Rita Oladele

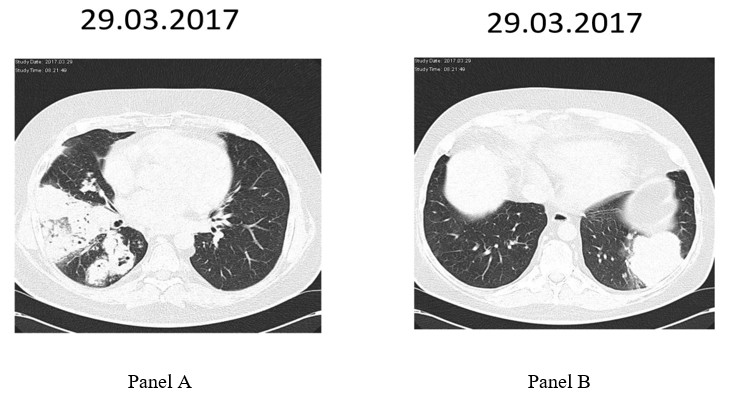

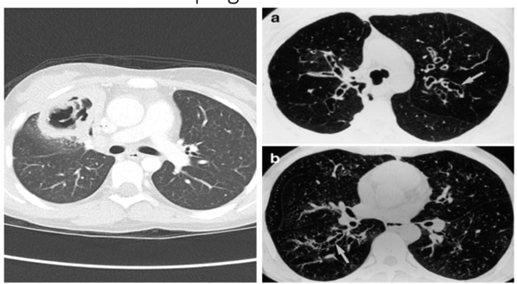

*Image is representative and is not of the actual patient.

Case Presentation

A 17-year-old male with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) presented to the emergency room 10 days post-last chemotherapy due to persistent fever (38.2°C–38.8°C), dyspnea, and cough. He had received a regular course of chemotherapy (daunorubicin, cystine arabinoside, L-asparaginase) in the previous 4 months. Physical examination revealed a body temperature of 38.4°C, blood pressure of 95/65 mm Hg, a pulse of 104 beats per minute, respiratory rate of 24 breaths per minute, and oxygen saturation of 95% (2 L O2/m was administered by nasal cannula). His initial laboratory results revealed leukocytosis (12 × 109/L, 94% neutrophils), anemia (Hemoglobin: 8.0 g/dL), and thrombocytopenia (125,000 platelets/uL). His procalcitonin was 9.1 μg/L. His chest X-ray appeared normal.

Past medical history revealed he had repeated (three) episodes of hospital-acquired infections due to an extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae bloodstream infection, which was managed with meropenem (2g BD 8 hourly) plus colistin (150 mg BD). He also had documented severe neutropenia (total WBC count: 500 cells/ mm3). He had been given voriconazole and trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole as prophylaxis during earlier admissions.

He was subsequently admitted into the oncology ward and placed on voriconazole and linezolid plus piperacillin-tazobactam. A bone marrow aspirate examination was also done to assess leukemic burden, and the results revealed a morphologic leukemia-free state.