24-Year-Old Man Referred to the Clinic with Severe Respiratory Symptoms, Extensive Skin Lesions, and Fever

Presented by Drs Beatriz L. Gómez, and Angela M. Tobón.

*Image is representative and is not of the actual patient.

Case Presentation

A 24-year-old male patient is referred to a regional hospital after 3 months of productive cough, dyspnea at rest, fever, anorexia, and weight loss. One month prior to consultation, he noted the appearance of non-painful skin lesions, principally on the face and extremities. He is an indigenous farmer and is a resident of a reservation in Colombia. He reports no previous diseases.

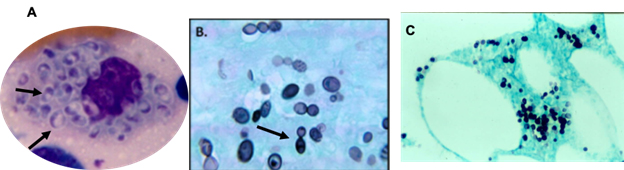

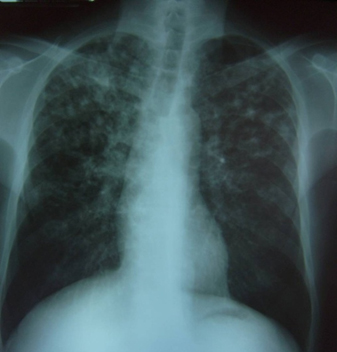

At physical examination, the patient is found to be hypotensive and tachycardic, with a respiratory rate of 22 breaths per minute and mucocutaneous pallor. Right cervical lymph node enlargement is noted. Pulmonary auscultation reveals few rhonchi in the right hemithorax. Abdomen examination shows hepatomegaly of 4 cm below the right costal margin that is painful. The neurological examination is normal. On the skin of the face and extremities are found multiple lesions in different stages of evolution: papules, vesicles, ulcers, and scabs/crusts (see Figure 1). The chest X-ray shows diffuse nodular interstitial infiltrates, no consolidation, and no pleural effusion (see chest X-ray Figure 2). Laboratory test results are shown in Table 1.

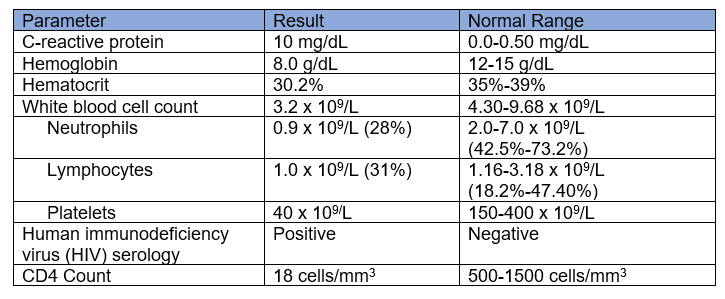

Table 1. Laboratory test results

Figure 1. Skin lesions on the face and ear at different clinical stages: papules, ulcers, and scabs/crusts. Image courtesy of Angela M. Tobón.

Figure 2. Chest X-ray: Bilateral nodular interstitial infiltrate, predominantly in the upper fields, no consolidation, no pleural effusion. Image courtesy of Angela M. Tobón.